Help with my account or courses

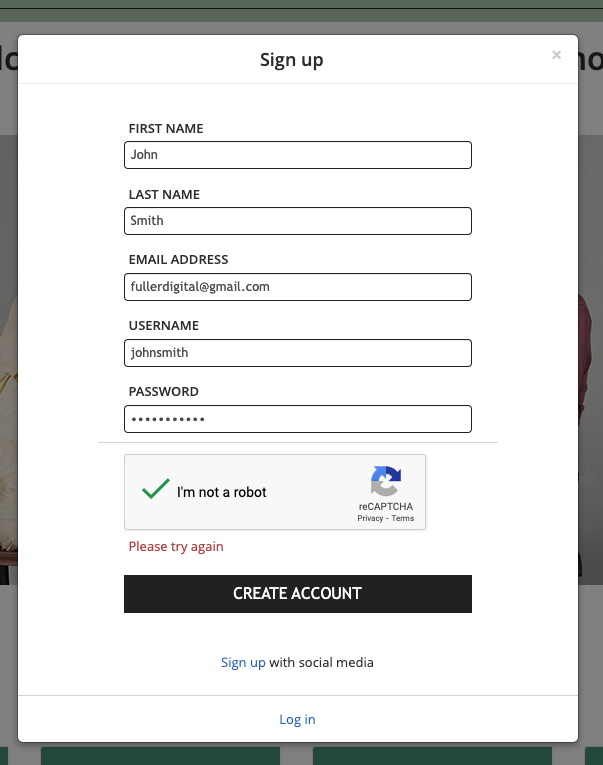

In order to sign up for an account for the Autistics' Guide to Adulthood, you will need to navigate to https://autisticsguide.talentlms.com/ Select 'Sign Up' from the menu and complete all fields, including selecting the re-captcha check box.

After completing all fields, select 'Create Account'.

A confirmation email will be sent to you once you've completed the sign up form, please check your junk mail folder if you haven't received it. You do not need this email to verify for your account and upon sign up you will be logged in.

If you have any issues with creating an account, please contact us via email autisticsguide@autismsa.org.au

After completing all fields, select 'Create Account'.

A confirmation email will be sent to you once you've completed the sign up form, please check your junk mail folder if you haven't received it. You do not need this email to verify for your account and upon sign up you will be logged in.

If you have any issues with creating an account, please contact us via email autisticsguide@autismsa.org.au

After completing all fields, select 'Create Account'.

A confirmation email will be sent to you once you've completed the sign up form, please check your junk mail folder if you haven't received it. You do not need this email to verify for your account and upon sign up you will be logged in.

If you have any issues with creating an account, please contact us via email autisticsguide@autismsa.org.au

After completing all fields, select 'Create Account'.

A confirmation email will be sent to you once you've completed the sign up form, please check your junk mail folder if you haven't received it. You do not need this email to verify for your account and upon sign up you will be logged in.

If you have any issues with creating an account, please contact us via email autisticsguide@autismsa.org.au

If you have any issues creating your account, please contact us as autisticsguide@autismsa.org.au. To help our team identify the issue, please attach any relevant screenshots to show the error you are experiencing.

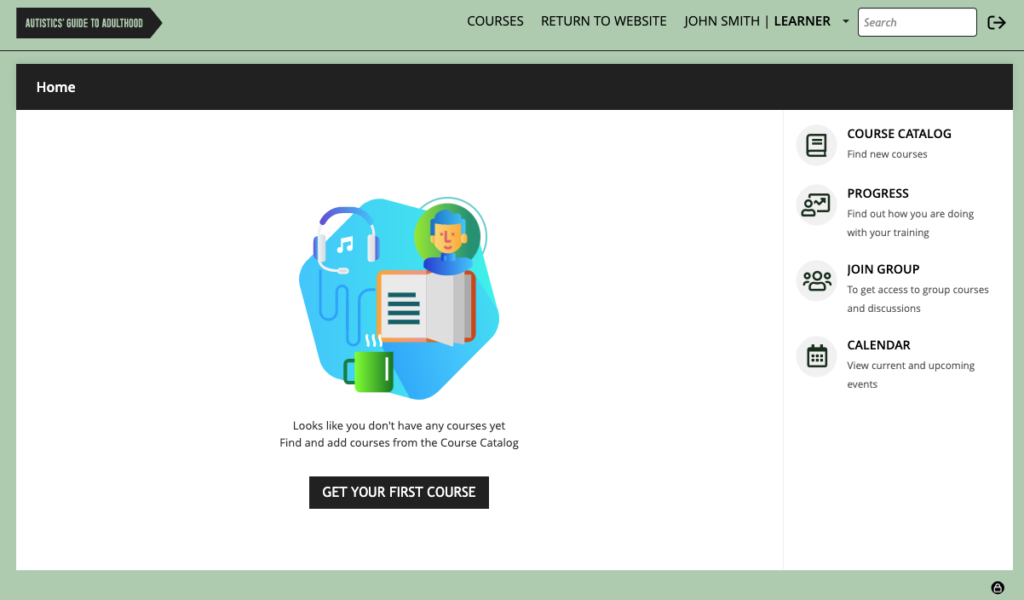

Once you have created an account and are logged in, you will see your dashboard. When you first sign up, you will not have any courses in your catalogue, as you will need to select each of the courses you would like to undertake. Below is what an empty catalogue looks like:

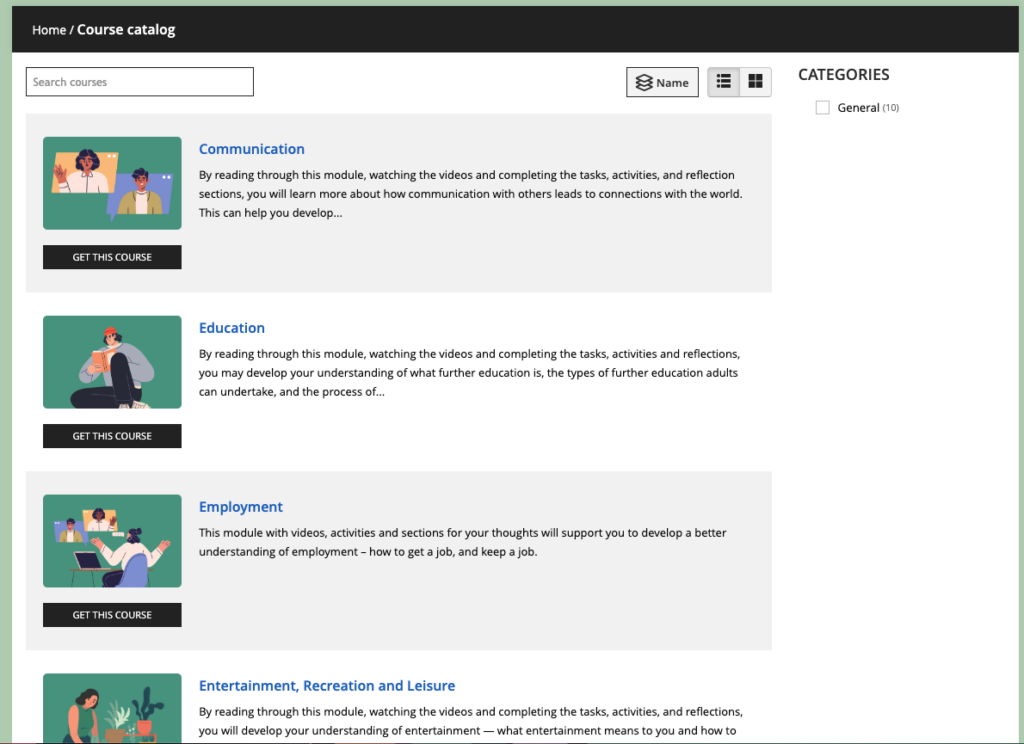

Select 'GET YOUR FIRST COURSE'. This will take you to a list of courses available that have been created for the Autistics' Guide to Adulthood. As per below, you can review the list and select the courses you wish to complete. They will then be added to your course catalogue.

Select 'GET YOUR FIRST COURSE'. This will take you to a list of courses available that have been created for the Autistics' Guide to Adulthood. As per below, you can review the list and select the courses you wish to complete. They will then be added to your course catalogue.

Select 'GET YOUR FIRST COURSE'. This will take you to a list of courses available that have been created for the Autistics' Guide to Adulthood. As per below, you can review the list and select the courses you wish to complete. They will then be added to your course catalogue.

Select 'GET YOUR FIRST COURSE'. This will take you to a list of courses available that have been created for the Autistics' Guide to Adulthood. As per below, you can review the list and select the courses you wish to complete. They will then be added to your course catalogue.

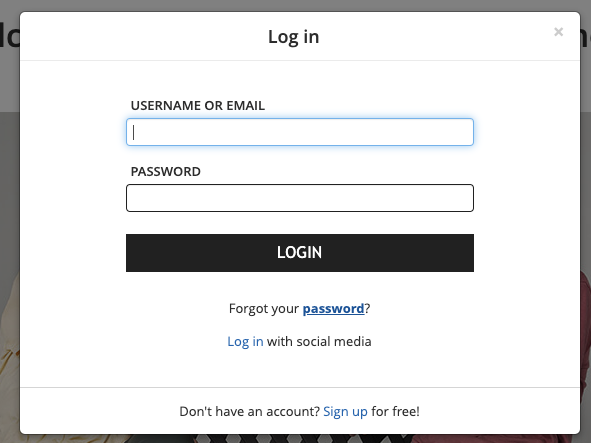

If you have forgotten your password, select the 'Forgot your password?' link below the login button:

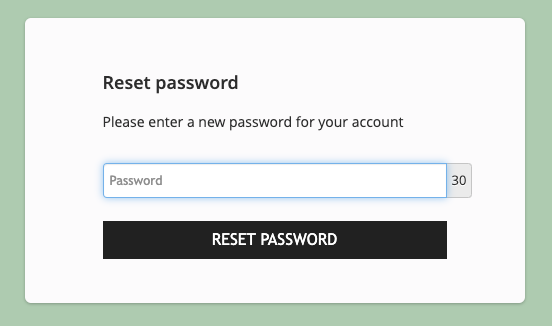

You will need to enter your username, this is your email address. If you have entered your registered email address, an email will be sent to you with a reset password link. Please check your spam folder for this email if you have not received it. The email will direct you to a new link where you can reset your password.

You will need to enter your username, this is your email address. If you have entered your registered email address, an email will be sent to you with a reset password link. Please check your spam folder for this email if you have not received it. The email will direct you to a new link where you can reset your password.

You will need to enter your username, this is your email address. If you have entered your registered email address, an email will be sent to you with a reset password link. Please check your spam folder for this email if you have not received it. The email will direct you to a new link where you can reset your password.

You will need to enter your username, this is your email address. If you have entered your registered email address, an email will be sent to you with a reset password link. Please check your spam folder for this email if you have not received it. The email will direct you to a new link where you can reset your password.

What is Autism?

Autism is a neurological developmental difference that influences (i) social interaction and social communication, and (ii) behaviour and processing sensory information. To break that down:

- Neurological means it’s an aspect of the individual’s nervous system; how the brain processes. This means autistic people process information in a different way, focusing more on some things and less on others than non-autistic people.

- Developmental difference means that the characteristics of autism primarily show up at a different stage of development, so many autistic people tend to start communicating, reading, engaging in self-care and so on, at a different pace to non-autistic people.

Autism is a neurological difference. Some find that autism negatively impacts their life in ways they don’t like and consider it a disability. Others regard it as a different way of thinking with its own strengths and drawbacks. Many celebrate their autism, treating it as a strength or even a super-power.

People on the autism spectrum may have co-occurring conditions, including some types of disabilities.

Under the DSM-IV, autism was divided into four distinct diagnostic criterias: Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder, Pervasive Developmental Disorder - Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS), and Childhood Disintegrative Disorder.

Since 2013, under the DSM-5, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is regarded as a spectrum, which recognises that everyone’s experience of autism is different across the diagnostic criteria.

Autism is a noun identifying the condition. Autistic is an adjective describing an autistic individual or a behaviour considered typical of autism. Otherwise, the two are the same.

Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler coined the term ‘autism’ in 1911, from the Greek ‘auto’ meaning ‘self’, originally as a symptom of schizophrenia.

Soviet child psychiatrist Grunya Sukhareva published the first clinical description of what is recognised as autism in 1925.

American child psychiatrist Leo Kanner defined ‘autism’ as it is used in the modern world in 1943.

And Austrian child psychiatrist Hans Asperger described the type of autism known as Asperger’s Syndrome in 1944.

An Autism Diagnosis

A good place to start is to communicate with your general practitioner (GP) or contact your state or territory’s autism association. They can provide you information about the autism assessment process, relevant to your state or territory. The Spectrum also provides information on the diagnostic process in Australian and can be a good place to start.

You can seek an autism diagnosis at any age.

That depends on why you want a diagnosis.

Many individuals find knowing they are autistic brings them peace of mind and a better understanding of themselves and their experiences. Others identify that a diagnosis may support them to access a range of support and services that they desire, such as NDIS support.

However, many who suspect they are autistic, but see no advantage or benefit from a formal diagnosis, are quite happy to leave it as an open question. This is often referred to as self-identifying.

Generally, referrals for adult diagnosis are made by the adults themselves, or by their parents or a family member or by their partner with consent.

Discussing your thoughts with a GP or relevant professional can be also useful prior to referral, as your health care professional may make referrals to undertake a psychological or psychiatric assessment. A speech therapist could also be consulted to assess your social communication skills.

Contact your state or territory’s autism association for options in your area.

The cost of getting an assessment varies according to age, location, and provider. It also changes over time. Contact your state or territory’s autism association or other preferred provider to find out what the current rates are and which providers will assess adults.

Why Autism?

Significant research has been conducted all over the world into the causes of autism.

For many types of autism, genetics seem to be a significant influence. For other types, the causes are unknown.

Some types of autism seem to have a direct genetic component. This can be seen in the increased prevalence of autism among relatives:

- General population – 1% chance of autism;

- Aunts, uncles, cousins of an autistic individual – 2-3% chance of autism;

- Siblings and non-identical twin of an autistic individual – 10% chance of autism;

- Identical twin of an autistic individual – 80% chance of autism.

There are some genetic syndromes associated with autism, such as Rett Syndrome or Fragile X Syndrome, in which the genetic cause is known. Researchers have identified over a hundred genes that influence neurological development that may have some influence on whether someone will be autistic. There are some organisations that do genetic testing that identify the specific genetics that caused autism for an individual, through in Australian, this is not widely done.

A 20-year study, the largest of its kind, comprehensively invalidated claims that the MMR vaccine increases the risk of developing autism. The research, performed at the Statens Serum Institut (SSI), tracked 657,461 children born between 1999 and 2010 from 12 months of age until August 2013, and included 31,619 who had not received the (measles, mumps and rubella) MMR vaccine.

It found that autism spectrum disorder (ASD) occurred equally in both sets of children, leading the study’s authors to conclude that the MMR vaccine does not increase the risk of developing autism.

Characteristics of Autism

Autism is a neurological developmental difference that influences (i) social interaction and social communication, and (ii) behaviour and processing sensory information.

To break that down:

- Neurological means it’s an aspect of the individual’s nervous system; how the brain processes. This means autistic people process information in a different way, focusing more on some things and less on others than non-autistic people.

- Developmental difference means that the signs of autism primarily show up in a different pace of development, so many autistic people tend to start communicating, reading, engaging in self-care and so on to a different schedule than non-autistic people.

Babies and young children develop at their own pace, and in different ways, with each developmental milestone coming in its own ‘average’ range. If these milestones are not met in a particular timeframe, or order, that may suggest the child has a developmental delay, autism could explain the atypical development.

A guide to the early characteristics of autism can be found at The Spectrum website.

Though autism is present from birth, sometimes it may not become apparent until later in life. A guide to characteristics of autism that may occur in teenagers can be found at The Spectrum website.

Since autistics process information slightly differently to non-autistics, the two don’t automatically get into synch when communicating. It’s like autistics need to learn a second language to communicate with non-autistics. And, like anyone speaking a newly-acquired second language, autistic individuals may miss things like subtleties, allusions, idioms, and the way that things like tone and body language can modify a message, that others take for granted. This often leads to awkwardness, misunderstandings, and withdrawal.

Many autistics report they find it easier to communicate with other autistics, since neuro-typicals tend to just ‘get’ various things, but since autistics are individuals, that doesn’t mean that such communication is always harmonious.

Since non-autistics constitute a majority of the population, most autistics have to communicate with non-autistics most of the time, so their challenges when doing so are one of the defining aspects of autism.

The term restricted and repetitive behaviours is used in the DSM-5 when outlining the diagnostic criteria for autism.

Autistic people display a range of actions and activities, including:

- repetitive sensory-motor behaviours, such as spinning in circles or flicking light switches;

- finds enjoyment and comfort in sameness;

- engage in self-injurious behaviours, such as nail biting or skin picking;

- have preferred sensory preferences, such as preferring certain fabrics or have a strong dislike for other sensory preferences such as certain smells;

- detailed interests, such as having a fascination with a specific number;

- have strong preferences for the way things are done, or the order in which they are done:

- use language in a repetitive manner;

- have a particular focussed interest, often acquiring extensive knowledge and expertise in.

Autism and Co-Occurring Conditions

OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder) is an anxiety disorder effecting someone’s mental health and autism is a neuro developmental difference. They are different conditions. About 8.9% of autistic individuals have OCD as a co-occurring condition.

An autistic individual that has a co-occurring of Savant Syndrome and intellectual disability.

It is defined as someone who has an intellectual disability, that poses exceptional cognitive skills in a particular area. The skills that savants excel at are generally related to memory. This may include rapid calculation, artistic ability, map making, or musical ability. Usually, only one exceptional skill is present. There is an increased prevalence of Savant Syndrome within the Autistic community then the general population.

Epilepsy occurs in about 3% of the Australian population. It co-occurs in the autistic community at a higher prevalence rate of between 5% and 46%.

Everyone has a different sensory profile, meaning their brains process information from their senses to different degrees, paying more attention to information from some senses and less to others.

In autistic individuals, the differences in their sensory profile can be significant. They can be very high sensitivity to some things like noise, light, texture, temperature, smell, and so on. This means they can find certain environments overwhelming, even though their non-autistic peers feel perfectly comfortable in them. At the same time, individuals can also have very low sensitivity to other things, such as pain, cold, or strong flavours, meaning individuals can endure situations non-autistics find intolerable.

Support and Services

Each state or territory has its own autism association:

- Australian Capital Territory – Mary Mead Autism Centre

- New South Wales – Aspect

- Northern Territory – Autism NT

- Queensland – Autism QLD

- South Australia – Autism SA

- Tasmania – Autism TAS

- Victoria – AMAZE

- Western Australia – Autism Western Australia

Contact your state or territory’s autism association who can provide information on local service providers, events, organisations, and fundraisers.

More specifically:

- Reframing Autism — works with autistic people and posts on Facebook and Linkedin with helpful and positive messages about autism.

- Autism Self Advocacy Network Australia and New Zealand — the peak body for autism self advocacy in Australia and New Zealand.

- The Autistic Realm Australia (TARA) — is an Australian charity run by autistic people.

- The iCan Network — for support in schools and mentoring. Based in Victoria.

- Yellow Ladybugs — support for autistic girls, women, and gender diverse individuals.

- Different Journeys — an autism charity for teenagers and adults.

The Occupational Therapy Australia website has a ‘Find an OT’ feature that lists registered occupational therapists in Australia.

The Speech Pathology Australia website has a ‘Find a Speech Pathologist’ feature that lists registered speech pathologists in Australia.

The Australian Psychological Society website has a ‘Find a psychologist’ feature that lists registered psychologists in Australia.

How was the Project Developed?

In 2019 Autism SA received funding from the Australian Government through an Information Linkages and Capacity Building (ILC) grant to develop a series of on-line modules for autistic adults, relevant to the Australian Autistics communities wants and desires. A project team, consisting of neurodivergent, autistic and professionals was formed. Extensive community engagement was carried out, including establishing a National Advisory Group to support the development of the project from commencement to launch.

Co-design brings relevant stakeholders together to design new products, services, and policies.

The Autistics’ Guide to Adulthood used a co-design process to plan for, develop and implement the project.

Members from the Autistic community were employed as part of the Project Team- the team responsible for developing all content for the project, including the copywrite, infographics and videos as well as other supporting material.

Extensive community engagement with the Autistic community, including a national survey where more than 400 autistic adults partook, was completed to clearly identify the needs and desires of the border Australian Autistic community. Members that specialised in certain areas were also interviewed to support the development of the modules.

Additionally, a National Advisory Group composed of diverse autistics from across Australia, was formed through an expression of interest process. The National Advisory Group supported the development and review of all content, and many other aspects of the project including the branding and the development of the name and logo for the project.

Together the Autistics’ Guide to Adulthood was created.

The National Advisory Group was formed in August 2020, shortly after the project was launched. It has been involved in a range of aspects of the project, from developing the name (Autistics’ Guide to Adulthood), influencing the brand, developing the pre and post survey questions, co-developing the measure used in the independent evaluation, supporting the development of all the content for the modules, supporting the development of the infographics, developing the videos, and other material used. In addition the National Advisory Group supported with the development of the community engagement plan, including the language and tone guide for the project, the marketing and promotional plan and media release and have been essential in supporting the overall success of the project.

An expression of interest seeking autistic individuals from across Australia was developed and distributed through various Autistic communities and groups communication channels. Every adult who responded and wanted to be involved, were provided with the opportunity to be involved.

Members met monthly, online and could contribute through the online meeting, emails or texts.

An honorarium was awarded for their input. Serving on the National Advisory Group supported the co-production of the project, from developing and reviewing content, to supporting the development of the branding. It involved attending meetings, reviewing material and sharing experiences.

Over the course of the project, some members changed, but the committee remained at around 10 members throughout the project.

The Autistics' Guide to Adulthood thanks all members for their contribution and their support in co-developing the project.

The adult autistic community communicated to Autism SA that they felt that there was a lack of relevant supports and services specifically developed for adults. Many felt that resources were developed for children and had been modified to support adults.

The Project Team used the below process to identify the material included in the Autistics’ Guide to Adulthood:

- Literature review - identified the Australian communities wants and needs outlined in research.

- A National survey- identified the broader Autistics communities needs and wants.

- Key Word Searches- were used to identify topics that people searched online for.

- Research on specific topics was completed.

- Resources and references including research, websites, books, videos, internal resources (Adult Social Program) were used to support the development of the content.

- Interviews with autistic experts were conducted and included in the content.

- The National Advisory Group supported the development of the modules, and provided personal insight and experiences throughout the modules.

- The expertise of the Content Writers employed - autistic and professional - was utilised.